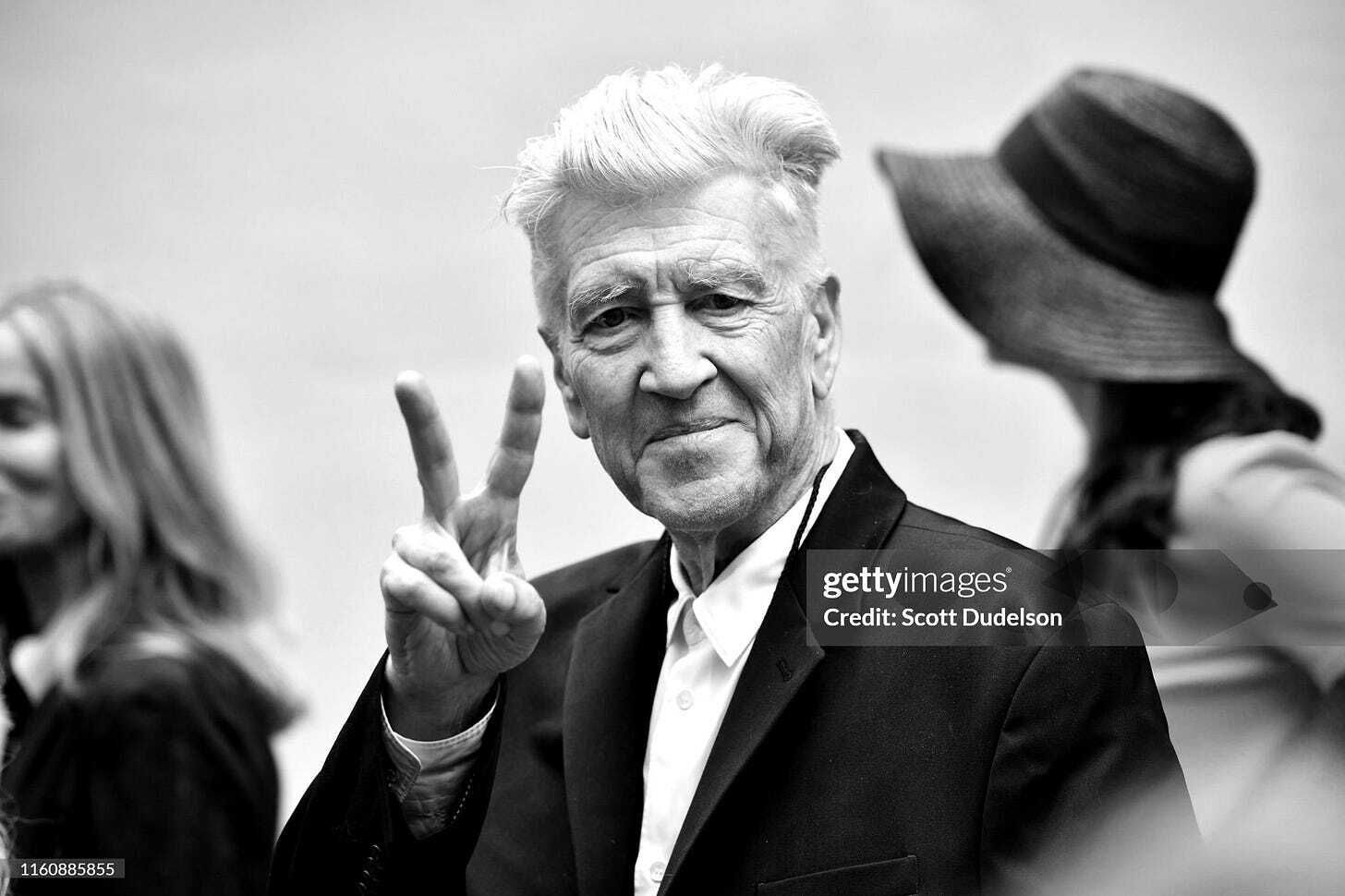

David Lynch died today. He was 78 years old. Monday would have been his 79th birthday.

I don’t know when or where or how I learned who David was, but I can tell you for sure that I learned about the style before I learned about the man. “Lynchian” was ubiquitous in film commentary, a world I accessed — as a kid — through Siskel & Ebert’s At the Movies or through movie trailers or through my dad. As I grew older, my hunger for movies grew with me. Commercial fair, mostly, with new young auteurs becoming my heros: Nolan, the Wachowski’s, Soderbergh, M. Night Shyamalan, Edgar Wright, on and on. Studio comedies, R-rated especially, were flourishing, and their scripts became my lexicon. I made a movie review wordpress site, scoring movies on a scale, based on technical craft and other “quantifiable measures”. I was a film bro with a narrow scope. I don’t look back on myself with any judgement — I was consuming things I loved, and I didn’t know just how many other things were out there.

I moved to Oregon when I was about to turn 25. I had started to broaden my movie viewing habits, but the boom really happened when I came out here and made a hundred new friends, who introduced me to the world beyond the cornfields and shopping malls of rural Illinois. I was done with school and in a new place, and I had a lot of time on my hands. That’s when I started to discover David Lynch.

Twin Peaks was probably what did it. It was available on Netflix at one point, and everyone decided that was the time to take the leap. It was immediately and obviously transcendent, and immediately obvious that this was a creator who would have to push against regulations and standards and tastes of the industry he was working within to express what he was feeling in the ways he wanted to express them.

I remember where I was when I watched Gotta Light?, the eighth episode of the third season of Twin Peaks in 2017: alone in my house, all of the lights off, with studio-level headphones plugged into the TV. I have never been more prepared to give everything to an episode of TV. It gave me something back, the likes of which I’ve never felt, before or after.

I watched Dune with some friends before the new Denis Villeneuve version was released in 2021. I might have fallen asleep. It was remarkable regardless.

I saw Mulholland Drive at my favorite theater in Portland with a friend from LA, an important link to my growth as an art consumer and as an adult. The film was deafening. I don’t just mean that hyperbolically: when the first reel started rolling, the roaring engine careening around the curves of the titular road were unbearable, viewers whipping their heads left-and-right, desperately searching for someone who could help them, our ears and bodies pounding and pounded by sound waves. They quickly turned the volume down, but the pounding and rattling of bodies did not stop.

I saw Blue Velvet at the same theater at midnight a few months later, a screening for volunteers that had to wait for all of the normal showings to conclude. I battled against sleep as Lynch showed me something shapeless, nameless, unbelievable. It was impossible to tell what was him, and what was my hallucinatory fatigue. He’d probably love to hear that.

As I spend my days combing through older movies, falling in love with new styles and creators, I find countless connections and influences across the one-hundred years of the art-form. Just yesterday I watched a movie from 1957 that was more prescient and affecting and entertaining than any movie I’ve seen made in the last five years. There is so much echoing off the halls of filmmaking and Hollywood.

I haven’t yet discovered a filmmaker that matches David Lynch’s un-match-ability. His purity of vision created some of the strongest and longest lasting bonds to his work that I’ve ever seen from film-goers. As a kid I was told his movies were pretentious. As an older-now kid, I see that diagnosis as shameful and hollow. I have endlessly looked forward to seeing everything he has made, and I loved seeing it while he was around, holding down the fort in his L.A. home, giving weather updates and surely reading, writing, and thinking about what was next. He was endlessly capable of saying anything, cutting through the noise of industries and know-it-alls. He seemed capable of anything.

I am really sad, but I find humor and levity in the thought that, if anyone believed in realms that we can exist in outside our bodies, our conscious minds, our selves, it seems to be David. He held our hands and showed us, several times, that there is more to the universe than what we can see, hear, taste, feel. Only he knows what’s next for him.

Or, as a friend put it in a text just now:

He died today. He was nearly 79 years old. His city was on fire. People watched on TV as livelihoods were destroyed, then they were served ads for AI search engines and Burger King chicken fries. Everything was lost. TV’s turned off.

How Lynchian.